One of the biggest questions we get asked by readers after they see the wealth of information we packed into a single book, is how did we wade through it all? How did we decide what was factual enough to include and what else was just a good story? That in turn leads us to another misconception we’ve heard from some: that because some of co-founder Nolan Bushnell’s past stories and versions of events did not make it in to the book, that he was never interviewed. Nothing could be further from the truth of course, they just simply didn’t stand up to scrutiny as you’ll see in the later example in this post.

First and foremost, let me say that we have the up-most respect for every person who made Atari what it was, and always conducted ourselves with the up-most professionalism while conducting interviews and when later reviewing information for validation. Our goal with Atari Inc. – Business Is Fun was to get as accurate an accounting as humanly possible, because the fans of the brand demanded it. This meant following a rigid process for everyone we interviewed across the board, no matter how high or low on the corporate totem they were. That process was:

First and foremost, let me say that we have the up-most respect for every person who made Atari what it was, and always conducted ourselves with the up-most professionalism while conducting interviews and when later reviewing information for validation. Our goal with Atari Inc. – Business Is Fun was to get as accurate an accounting as humanly possible, because the fans of the brand demanded it. This meant following a rigid process for everyone we interviewed across the board, no matter how high or low on the corporate totem they were. That process was:

1) Information needed to be corroborated by at least one to two other sources. That source could be an interview with someone else, an internal memo, an engineering log, an internal email we have a log of, other paperwork, etc.

2) When interviewing others, we were very careful not to “lead the witness” or produce cross-contamination. That meant not trying to ask “Is it true such and such happened,” or “So and so said…” but rather allow them to bring it up themselves to produce a blind validation. If the subject never came up and we had to introduce it to the conversation (which happened once in a great while), it was asked in as minimal a manner as possible. Such as “We heard you guys tried to tie up multiple chip sources to block out competitors. Can you elaborate on this?”

3) In the case that we couldn’t find corroboration but the information seemed plausible, we included it in the book with “According to…”

4) In the case where it was not only uncorroborated, but refuted by other verifiable sources, we did not include it.

5) Before publication we also gave people we interviewed a chance to read over the book sections that cover them. They were given the chance to elaborate, contest, or confirm the material. In cases where we had something wrong, we corrected the info (after repeating the previous four steps). If the contested material simply did not vet because of the previous four steps, we discussed it with the subject and showed why, giving them a chance to further respond. (For the bulk of the material in the book it rarely had to go this far).

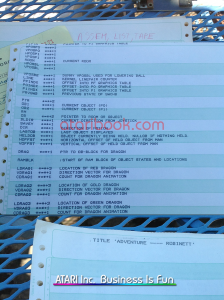

Let me tell you right now, without all the resources listed in step 1, this book would have never been possible (or would have been a very different book – probably much more in line with earlier efforts to chronicle Atari). We can’t thank ex-Atari employees enough for their generosity in time and resources. Many sent us their engineering logs and business diaries they’ve held on to all these years, along with other paperwork, notebooks, diagrams and other mementos. The people we interviewed were also always available for us via phone and email to ask further questions (and in many cases I’m sure annoy them) in an attempt to clarify events.

Let me tell you right now, without all the resources listed in step 1, this book would have never been possible (or would have been a very different book – probably much more in line with earlier efforts to chronicle Atari). We can’t thank ex-Atari employees enough for their generosity in time and resources. Many sent us their engineering logs and business diaries they’ve held on to all these years, along with other paperwork, notebooks, diagrams and other mementos. The people we interviewed were also always available for us via phone and email to ask further questions (and in many cases I’m sure annoy them) in an attempt to clarify events.

Then there’s the large personal expenses of Curt and myself as we gathered further resources, such as additional internal documentation we paid for, legal document copies that were paid for, original backup tapes from Atari’s own mainframes (including internal emails, development directories, and more), prototypes, engineering diagrams, original artwork, press materials, paraphernalia and more. (All the material collected for this book is now part of the Atari Museum, an unprecedented archive of material belonging to Atari Inc.and Atari Corporation. Scott Evans’ collection of material from Atari Inc.’s and and Atari Games’ coin-op related history is the only other substantial collection of related material out there).

Though there were some high profile stories we certainly wanted to get to the bottom of, we did not set out to specifically debunk anyone or attempt to show them in a negative light. We approached everyone, no matter their position at Atari, with the same neutrality and initial acceptance of their graciously contributed stories and time. But as with many personal stories that people were asked to recount 20-some to 40 years after the fact, the facts weren’t always crystal clear – nor did they always hold up to the scrutiny mentioned above.

A first example

As an initial example, we were told a story by Ray Kassar that he had meetings with Steve Jobs in 1979 to have Atari buy Apple. He stated it got far enough that he proposed it to Warner Communications head Steve Ross (because Warner would need to fund it), who then nixed it.

As an initial example, we were told a story by Ray Kassar that he had meetings with Steve Jobs in 1979 to have Atari buy Apple. He stated it got far enough that he proposed it to Warner Communications head Steve Ross (because Warner would need to fund it), who then nixed it.

Unfortunately, we could not find supporting documentation or anyone else that had heard of the event, including the Warner Communications liaison to Atari, Manny Gerard. As the person in charge of overseeing Atari for Warner, Manny stated quite emphatically it never happened or he would have been a part of it, as Ray reported directly to him. He further stated that neither did his direct boss, Steve Ross, ever state anything about it to him.

This normal process chain is verifiable: You see, Manny’s job as Co-President of Warner Communications was to oversee Atari for Warner, and help guide the important subsidiary. A position and task easily verifiable by newspaper and magazine articles from the time, as well as interviews with other Atari Inc. management. Likewise, in further research we saw that Steve Ross didn’t circumvent Manny and get directly involved with Atari until things started crashing down in late ’82. Even when things were bad in ’78 and Nolan was declaring the 2600 dead, Steve Ross deferred to Manny and his decision on the matter as the person who was supposed to have his thumb on the pulse of Atari for Warner. And it was Manny who oversaw the putting of Nolan and others “on the beach” and the moving of Joe Keenan to Chairman of the Board and Ray to President of Atari in January 1979. Hitting a dead end on the validity of the story and seeing the plausibility in question in light of these facts, we decided not to include it in the book.

Part II of this topic will be up later this week, centering around “When did Nolan Bushnell see Spacewar! for the first time” as another example of the process.